“If you want to learn about a city, look at its walls.”

-Greek graffiti artist iNO

In springtime, the fields around Sderot are carpeted with red and yellow flowers swaying in the breeze. Yet the pastoral setting is at odds with drab concrete tenements rising up from the impoverished Israeli city under constant threat of attack.

Nowhere in Israel has been as heavily bombarded as Sderot. More than 8,600 rockets fired from Gaza, the Palestinian territory controlled by the Islamist group Hamas, have landed in and around the city since 2001 according to the local media center. Ten people have been killed by rocket fire in Sderot since June 2005 and dozens more have been injured. Psychological stress also takes its toll.

With just over a kilometer of fields separating it from the Gaza Strip, Sderot is an obvious target for Palestinian militants whose stated aim is to destroy Israel. The most intense bombardments came during Operation Cast Lead in 2008-2009, when Israel launched an attack on Gaza, beginning with a week of air strikes and shelling, followed by a land invasion. Hamas and its allies responded by firing rockets and mortars into Israel during the three-week conflict, which killed an estimated 1,400 Palestinians and 13 Israelis.

Israel’s Iron Dome defense system that destroys incoming rockets does not offer full protection to Sderot. When a “code red” alarm crackles over the city’s loudspeakers, the roughly 25,000 residents have 15 seconds to seek shelter from incoming projectiles.

“Having 15 seconds to run for your life is hard to understand or explain,” said Noam Bedein, director of the Sderot Media Center. “Routine life is a bit absurd, but you accept it.”

The situation affects people’s lives in all sorts of ways. Seat belts are left unfastened to allow for a quick escape from vehicles, and residents travel to and from work, school, or shopping centers along routes offering protection in the form of blast walls and shelters.

The visual landscape of Sderot is shaped by some 200 bomb shelters scattered around the city. Many buildings feature metal windows and walls and roofs made from reinforced concrete. Areas from playgrounds to roadside objects can function as shelters.

From 2009-2013 the Israeli government spent almost $150-million building shelters for every residence, the Sderot media centre said. They exist to save lives, but the concrete slabs are an eyesore in a city already lacking architectural grace.

Yet the hardscrabble town has applied the adage of making art not war to turn the destructive threat into a source of creative inspiration.

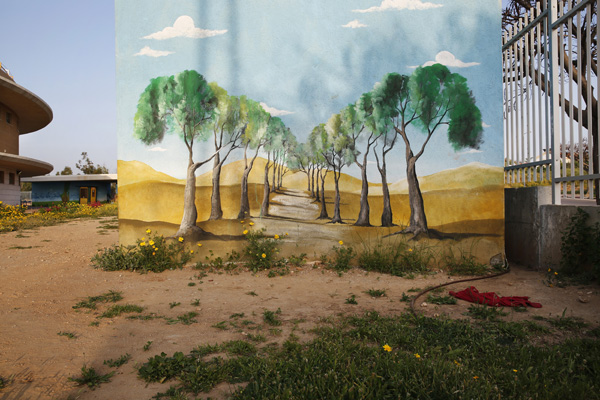

A city initiative in recent years brought artists to paint many of the bomb shelters. School yards feature block-shaped shelters or blast walls illustrated with idyllic nature scenes, urban graffiti, or primary colors. One public playground features a giant black, green, and orange caterpillar made from concrete tubing that doubles as a shelter.

“Painting the bomb shelters makes the rocket reality a bit more normal even though it is completely abnormal,” said Bedein.

Sderot’s colorful bunkers are more than just a dash of make-up slapped on an ugly facade; they reflect the wellspring of creativity flowing from the town. Young musicians have used one of the town’s bomb shelters as a rock-and-roll club and the city exports recording artists at a rate almost as prolific as the rockets flying into it.

A documentary film, Sderot: Rock in the Red Zone, chronicled the many musicians originating from the city, from a singer who won a Pop-Idol style Israeli TV show to the frontman of a band for Israel’s 2007 entry to the Eurovision Song Contest.

Local author and poet Shimon Adaf, the son of Moroccan immigrants, also won last year’s Sapiro prize, Israel’s top literary award. One of his poems about Sderot includes the following lines:

The Skies make peace amongst themselves and fall

On a hard earned workingman’s town

Through industrial shadows, smoke sheets,

My childhood fears jump me, like

Armed assailants from the back alley of a forsaken night.

In this embattled atmosphere, many of Sderot’s residents – particularly its children – exhibit symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Music, writing, and even the painting of the bomb shelters has provided an outlet for expression and healing, according to Bedein, who said the city has invested in creative arts programs, including drama therapy.

“An entire community is coping through these tools and expressing themselves through art,” he said. “If you don’t express yourself and let things out, you keep them inside and it can be very damaging without even realizing it.”

The harsh realities faced by Sderot’s residents can perhaps be summed up by a few lines from another of Adaf’s poems.

And between us there is nothing but

a great cycle of blood and stars

that traps us without end

in its turning, like a

blender.

***

Photographer’s note: The images in this series were taken at sundown, often on Friday or Saturday, when the streets were mostly devoid of people and cars. The lack of human presence was intended to create a sense of foreboding and tension suggesting that all is not quite right. The tilt function of a tilt-shift lens was used on some images to correct the converging parallel lines caused by photographing buildings from ground level.

http://blogs.reuters.com/photographers-blog/2014/04/28/15-seconds/