|

|

|

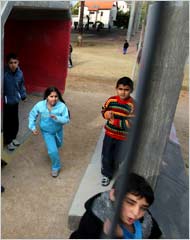

Rina Castelnuovo for The New York Times

Two loud supersonic booms sent Raziel Sasson to look for cover as he was showing his scarred neighborhood to a visitor. |

SDEROT, Israel – Less than two months ago, Raziel Sasson emerged from his rocket-proof closet, willing now to sleep just outside it, with the rest of his family, on mattresses circled on the living room floor. But Razi, 13, still wakes his father up three times a night, afraid to walk alone to the bathroom.

Families who can no longer endure the attacks move. Advertisements for their homes hang on the window of a realtor’s office at bargain prices.

The first Qassam rockets that hit Sderot were turned into a city sculpture. But since then the rockets have grown larger and come more frequently.

|

| The New York Times |

Four years ago, Razi was climbing a tree when a Qassam rocket, fired from nearby Gaza, flew over his head and exploded nearby. He remembers the spinning contrail of the crude rocket and its fierce whistle. The blast blew him eight yards to the ground.

Sderot, a working-class town of mainly North African immigrants less than two miles from Gaza, has been hit over the past four years with some 2,000 rockets of improving range and explosive power – 22 in the last eight days. Eight Sderot civilians have been killed by the rockets; Razi has seen 15 therapists.

“He wouldn’t leave the house to go to school for a year,” said his mother, Shula. One of his older brothers, Rafi, 22, used his army exit pay to build Razi a bomb shelter in the living room, a concrete cocoon with a steel door.

Across the border in Gaza, life is wretched for Palestinians. But as President Bush prepares to arrive in Jerusalem on Wednesday for the first time since taking office, to spur peace talks between Israel and the Palestinian president, he will hear a lot about the Qassams.

|

|

Rina Castelnuovo for The New York Times |

For many Israelis, Sderot (pronounced stay-ROTE) embodies the fears of what happens when they pulled back from occupied land, as they did from all of Gaza more than two years ago – it turns into a staging ground for attacks by extremist Palestinians that a peace treaty will not stop.

“When Bush comes, he should come to Sderot,” said Razi’s father, Moshe, 49, who works as a prison warden in Beersheba.

The problems of Sderot – and of a Gaza run by Hamas, considered a terrorist group by Israel and the United States – are at the heart of Israel’s security concerns. But those concerns, like Hamas itself, are present only in the abstract in the American-led peace effort, which features negotiations between Israel and the Palestinian president, Mahmoud Abbas of Fatah, who has no control over Hamas or Gaza.

The Israeli Army has installed a system to warn of incoming rockets. Suddenly, throughout a placid, sunny Sderot, a woman’s tinny voice echoes on loudspeakers, intoning, “Tseva Adom, Tseva Adom,” or “Color Red.”

The lives of people here now revolve around that alert, which gives them 15 to 20 seconds to find shelter. Sderot seems at first like any other southern Israeli town – the same shawarma and falafel shops, the same supermarkets, the same traffic circles, the same palms and Royal Poinciana, or flame trees, the same little market twice a week.

|

|

Rina Castelnuovo for The New York Times

Families who can no longer endure the attacks move. Advertisements for their homes hang on the window of a realtor’s office at bargain prices. |

But already quiet, with the population down unofficially to perhaps 17,000 from 24,000, the people of Sderot live in a most un-Israeli hush, so they can hear the alerts. The vendor in the market who sits on a stool and yells out the prices of his cheap underwear has been told to stop using a megaphone. People sleep with the heating system off and a window open on the coldest night. There is no Muzak in the grocery store, and people keep their car windows open and their radios and televisions on low volume, even in the town’s few bars or pubs.

They take quick showers, afraid to miss an alert, no longer sleep in upstairs bedrooms and avoid public places at what are considered peak Qassam times. And when the alert sounds, people drop everything, including their unpaid groceries in the aisles, costing Daniel Dahan more than $100 a day, he said. He owns Super Dahan, the grocery his father started. They run to one of the square concrete shelters, known as betonadas, after the word for cement, that increasingly dot the town. Then they pull out their phones, to check on their children.

“What kind of life is this, when you can’t even make your home safe for your children?” Ms. Sasson asked. Their house, like most in Sderot, was built before the Persian Gulf war of 1991 and lacks a safe room, protected against rocket attack. Under political pressure, the government has been reinforcing schools and building betonadas, and it recently began a survey to see how much it would cost to provide every home a safe room.

One of the surveyors, working under contract, said that in her third of Sderot, there were 1,700 houses and apartments without safe rooms; it would cost an estimated $25,000 each to install the household shelters.

|

|

Rina Castelnuovo for The New York Times

The first Qassam rockets that hit Sderot were turned into a city sculpture. But since then the rockets have grown larger and come more frequently. |

The Sassons have another son, Aviran, 19, who just finished his basic army training. In May 2006, he was finishing his prayers at school when a Qassam landed in the classroom next door. It stuck in the floor but did not explode. Aviran, too, required therapy and tranquilizers.

A little more than three weeks ago, on Dec. 13, Ms. Sasson’s daughter Nofit, 21, was on the roof terrace hanging out laundry when she heard the red alert and then saw a Qassam whistling toward her. She ran screaming down the stairs; the rocket hit the house next door, exploding and then embedding itself in the wall between the houses, just next to canisters of bottled gas, shattering windows and cracking walls.

“Razi was on his bike,” Ms. Sasson said. “I heard the explosion and saw the smoke and ran to the door of the house, and I met him there. And I felt a huge pressure in my chest and I fell, and he started screaming and crying to see me on the ground.”

The emergency services rescued the woman next door, who was in a wheelchair, and brought Ms. Sasson to the trauma center, then to the hospital. They tracked down Mr. Sasson, whose boss arranged for someone to drive him home. Ms. Sasson was hospitalized for six days and remains on sedatives and blood thinner. She is trying to persuade the state insurance company to pay for her blood thinner, which costs $100 a month.

Mr. Sasson and relatives took care of Razi and Lise, 11, and after two days, brought the children to the treatment center; neither would go to sleep or turn out the light. Razi reverted to his shelter, but left the door ajar.

“I always took care of the kids, and now it reaches me,” Ms. Sasson said. With the demands of caring for the younger children, she cannot work, having been let go from different jobs for her inability to keep a fixed schedule.

She was born here, and has eight brothers and sisters, and feels bound to the city by family, her children and her mortgage in a place where property values have sunk. “My whole life is here,” she said. And then she said, “I’d leave if I could.” And then: “It seems there is no choice. If I leave, it will be with great pain.”

She looked over the holed wall to the ruined house next door.

“It’s too bad we can’t enjoy what we have,” Ms. Sasson said, almost pleading. “This is such a good town.”

In the quiet city center, surrounded by a choice of betonadas, a smiling Razi was riding his bike. During the alert that day, he said calmly, he ran to a shelter. Then, in the sky, there was the low sound of airplanes, and suddenly he was transformed, his body rigid, his eyes locked into a stare of panic. “Did you hear?” he asked urgently. “Did you hear?”

“They’re your planes, Israeli planes,” he was told, but he stayed rigid. “No, no,” he said. “They’ll shoot back,” and his eyes swiveled with fear, hunting for a shelter.